Roger Tory Peterson

"As a naturalist, Peterson has the soul of an artist and as an artist the soul of a naturalist."

Roger Tory Peterson’s signature contribution to the arc of the American Conservation Movement was the modern field guide. Trained as an artist, Peterson understood the power of art to inform, inspire and illuminate people about the natural world. His illustrated field guides allowed for easy, accurate identification in the field. The experience of using the field guide has helped millions of people across the globe really see the natural world. To be inspired by it. To fall in love with it. Throughout his multifaceted career, Peterson helped us to see the challenges, too – the devastating impacts of pesticides, habitat loss and other environmental ills. He also demonstrated that each and every one of us can make a difference in protecting the earth’s diversity of plants and animals.

Roger was born and raised in Jamestown, New York. From a young age, he was entranced by nature. At a time when children were not allowed outdoors after dark, a young Roger asked and was granted permission by the local chief of police to stay out late to collect moths. At the age of 11, he discovered a clump of feathers clinging to the side of a tree:

Roger was born and raised in Jamestown, New York. From a young age, he was entranced by nature. At a time when children were not allowed outdoors after dark, a young Roger asked and was granted permission by the local chief of police to stay out late to collect moths. At the age of 11, he discovered a clump of feathers clinging to the side of a tree:

“It was a [northern] flicker, tired from migration. The bird was sleeping…but I thought it was dead. I poked it with my finger. Instantly, this inert thing jerked its head around, looked at me wildly,, then took off in a flash of gold. It was like resurrection. What had seemed dead was very much alive. Ever since then, birds have seemed to me the most vivid expression of life.”

Like many in Jamestown at the time, Roger found his first employment in one of its many Swedish furniture manufactories. Skilled with a paintbrush, his job was to decorate Chinese lacquered cabinets. A supervisor encouraged him to pursue a career in art. Roger saved his money and moved to New York City to attend the Arts Student League and later the National Academy of Design. While there, Roger fed his other passion as a member of the Bronx County Bird Club and with regular visits to the Museum of Natural History to study its bird collection. Combining his love of art and birding, Roger came up with the idea for a guide to help bird lovers like him make quick and accurate bird identifications in the field. Published in 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, the initial run of 2,000 copies sold out instantly.

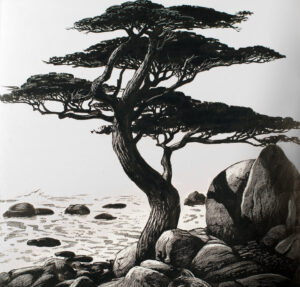

A Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America was revolutionary for its illustrations and “Peterson System” of field marks and classifications. Through five editions over the course of six decades, it sold millions of copies during Roger’s lifetime. Roger illustrated and authored or co-authored numerous field guides specific to other geographies, including, A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. He published field guides for native plants and other books about birds and nature, including Wild America. Co-authored with British ornithologist James Fisher, it is a chronicle of their 100-day, 30,000-mile field trip around the United States in search of birds. The book features exquisite black and white drawings by Roger — quite distinct from his field guide art and his fine art paintings of birds, they reflect Roger’s expansive capacity as an artist.

A Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America was revolutionary for its illustrations and “Peterson System” of field marks and classifications. Through five editions over the course of six decades, it sold millions of copies during Roger’s lifetime. Roger illustrated and authored or co-authored numerous field guides specific to other geographies, including, A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. He published field guides for native plants and other books about birds and nature, including Wild America. Co-authored with British ornithologist James Fisher, it is a chronicle of their 100-day, 30,000-mile field trip around the United States in search of birds. The book features exquisite black and white drawings by Roger — quite distinct from his field guide art and his fine art paintings of birds, they reflect Roger’s expansive capacity as an artist.

Roger’s field guide inspired many others — David Allen Sibley, Kenn Kaufman and Lillian Stokes, to name a very few. Which field guide is “best” is a hotly-debated topic. However, for many, the Peterson guide remains the definitive “bird bible.” In fact, the entire Peterson Series of field guides, currently published by Mariner Books, an imprint of Harper Collins, and covering a wide range of plants and animals, is the comprehensive go-to resource for introducing the next generation of nature lovers to the rich diversity of life on the planet.

Early in his career, following the publication of his first field guide, Roger worked for the Audubon Society. Like many of his time, Roger had been a Junior Audubon Club member, paying an annual dues of a dime. For nearly a decade, he served as Audubon’s educational director and art editor of Audubon Magazine. For many years following his departure from Audubon, he served on its board of directors and wrote and illustrated a regular column for the magazine, chronicling his world travels and weighing in on the critical conservation issues of his time. For instance, Roger was among the first to identify DDT as the cause of the catastrophic collapse in the population of ospreys, bald eagles and other bird species. In his testimony before a United States Senate Subcommittee, Roger reported shared that “The side effects of most [DDT] spraying programs go undocumented and more than 100 million birds are probably killed yearly. I just could not live without birds, frankly. I would hate to live in a lifeless world.”

Awards and Honors

- Distinguished Environmental Leadership Award, Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods, 1984

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, President Jimmy Carter, 1980

- Linné Gold Medal, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1976

- Honorary Fellow, The Zoological Society of London, 1975

- Conservation Achievement Award, National Wildlife Federation, 1975

- Distinguished Public Service Award of the Connecticut Bar Association, 1974

- The Explorers Medal, the Explorers Club, 1974

- Golden Key Award — Outstanding Teacher, National Council of State Education Associations, et al, 1974

- Doctor of Science, Colby College, 1974

- Joseph Wood Krutch Medal, Humane Society of the United States, 1973

- Gold Medal, World Wildlife Fund, 1972

- Audubon Conservation Medal, 1971

- Gold Medal of New Jersey Garden Clubs, 1970

- Francis Hutchinson gold Medal of Garden Club Members, 1970

- Doctor of Science, Wesleyan University, 1970

- Paul Bartsch Award, Audubon Naturalist Society, 1969

- Conservation Award, White Memorial Foundation, 1968

- Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence, Fallingwater Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, 1968

- Gold Medal, African Safari club of Philadelphia, 1968

- Arthur A. Allen Medal, Laboratory of Ornithology, Cornell University, 1967

- Doctor of Science, Fairfield University, 1967

- Doctor of Science, Allegheny College, 1967

- Doctor of Science, Ohio State University, 1962

- Gold Medal, New York Zoological Society, 1961

- Geoffrey St. Hilaire Gold Medal, French Natural History Society, 1958

- Doctor of Science, Franklin & Marshall College, 1952

- John Burroughs Medal for Exemplary Nature Writing, 1950

- Brewster Memorial Medal by American Ornithologists’ Union, 1944

Publications

Forthcoming

Awards Named for Roger Tory Peterson

The ABA Roger Tory Peterson Award Promoting the Cause of Birding, American Birding Association

Roger Tory Peterson Medal, Harvard Museum of Natural History

A Consideration of the Art of Roger Tory Peterson

Jon Boone

Background

Images of birds extend back into prehistory, symbolizing the profane and the sacred, political dominion and economic surety. By the early sixteenth century, European exploration of North America frequently included artists whose task was to pictorially record the flora and fauna of the New World. John White’s watercolors, for example, captured remarkable images of birds at Roanoke Island, Virginia in 1585. Early in the eighteenth century, Mark Catesby produced 263 paintings of birds for his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahamas [Illustration A], many of which Linnaeus used for the 10th edition of his System Naturae . Catesby’s pictures helped inform Lewis and Clark’s expedition nearly a hundred years later.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon had competitively created images of North American birds, with far-reaching effect. Wilson’s rustic illustrations for his eight volume American Ornithology were accompanied by text and poetry, providing information about each bird’s habits and habitats [B]. Audubon’s magnificent baroque paintings of birds [C], however, became entwined with the image of a new nation emerging from the wilderness, symbolizing both the nascent creative power of the United States and its ongoing paradoxical relationship with nature, torn as it continues to be between celebrating the natural world and ruthlessly subduing it.

As the twentieth century began, European sensibilities and burgeoning technologies, filtered through the American experience, had brought a closing to the vast North American frontier. A centuries-long march to the beat of seemingly inexhaustible abundance was replaced by a dawning recognition of limitation, of natural resources ravaged and lost. Passenger pigeons, once the most common bird in colonial America with numbers in the billions, had become extinct, along with several other prominent species. Many more were on the edge of extinction. The bodies of millions of native songbirds dangled around fashionable ladies’ millinery. Miners portentously used birds to assess air quality in coal shafts.

Habitat for many birds had also been transformed or eliminated. Most of the Eastern hardwood forests had been timbered while millions of acres of wetlands had been built over. Industrial development, including incipient factory farming practices, had altered much of the natural agricultural landscape. Coal, steel and railroads combined to forge giant cities like Chicago out of virtual wilderness in only a few decades. Electricity, refrigeration technology, and the internal combustion engine would soon conspire to bring new settlement in places so environmentally sensitive that most wildlife could not survive the intrusion.

In the midst of this onslaught, a few visionaries like Frederick Law Olmsted designed Central Park in New York City as a reminder about the importance of nature and as anodyne for the built environment. A half century later, Theodore Roosevelt endorsed the effort to expand public lands, in part to conserve wildlife habitat, culminating in the national park system. By 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act afforded migratory birds international protections, putting an end to birds as fashion adornments. These efforts soon took a backseat to world events. After the tumult of World War I and the inception of a global economic depression around 1930, much of Western Civilization was in crisis. Many Americans, nurtured by the spirit of self-reliance and rugged individualism, were now challenged by harsh circumstance. The doctrines of collectivism and even fascism began to have considerable appeal. In the United States, fully one-fourth of the work force was unemployed; millions had left a life on the farm for a job in the city. People whose parents and grandparents had once worked knowledgeably with

nature now felt strangely alienated from it.

Into the Breach

Into this breach stepped Roger Tory Peterson. His art and energy helped bridge the divide, using people’s interest in birds to spark a burgeoning international environmental consciousness. Peterson loved birds. His manifold representations of them were at the forefront of his creativity. Born in 1908 to immigrant parents in Jamestown, New York, he came as a teenager to New York City in the late 1920s to study art and birds. Within a few years, his skills as a graphic illustrator would blend seamlessly with his knowledge of birds and nature, enabling him to hit upon a “new plan” for making bird identification accessible to the masses in a way that encouraged individuals to teach themselves, enhancing their perceptual skills in the process. He led the educational outreach efforts of the fledgling National Audubon Society and the National Wildlife Federation, and he served as a consultant to, or as a member of the board of directors for, the most prestigious nature organizations in the world. At the time of his death in 1996, his many illustrations, drawings, paintings, photographs, films, speeches, and prose had made him into a talismanic symbol of the environmental movement, carrying forward the tradition of White, Catesby, Wilson (especially) and Audubon, and extending the ideas of Olmsted and Roosevelt about the importance of nature in our lives.

Peterson was at heart an educator whose talent for illustration enabled him to define the essence of things. Early on, his drawings and paintings for books, magazines, nature stamps and trading cards helped galvanize environmental public policy. His illustrations for Life magazine in the 1940s and his pictures for the 1964 book, The World of Birds, with James Fisher, are notable for biographers and environmental historians. In 1978, after a trip to Antarctica, he produced Penguins, with incomparable drawings of some of his favorite birds [D]. In his maturity, however, he began to think seriously about making art. Throughout the last two decades of his life, he defined himself primarily as an artist, in the process painting a series of “Audubonesque” bird portraits while helping to convene a serious dialog in the art community about art and nature. The public also identified with Peterson as a “bird artist,” and various media compared him favorably with Audubon.

In reality, Peterson has little in common with Audubon’s style and utter originality. Few of Peterson’s formal vignettes of birds have Audubon’s verve and swagger. Fewer still are as compelling as the bird vignettes of contemporaries such as Fenwick Lansdowne or the nature paintings of Robert Bateman, Thomas Quinn, Raymond Ching, and Carl Brenders, among others. To be sure, he created unforgettable images of Barn Swallows (1973), a Bald Eagle (1974), Barn Owls (1975), Snowy Owls (1976) [E], a Northern Mockingbird (1978), and, at the age of eighty-two, Brown Pelicans (1990) [F], perhaps, with Snowy Owls, his most indelible painting, challenging Audubon’s best. On the whole, however, these are decorous, convivial works testifying mainly to the skills of a consummate craftsman and the knowledge of a keen observer of nature.

For all his considerable achievements, this prolific man knew his essential legacy—and his artistic reputation–was lashed to the quality of the familiar Baedeker for birds he introduced in 1934. What Peterson and Audubon had in common was not their paintings but rather an artistic sensibility that visually captured the zeitgeist of their respective eras. The Art of the Field Guide Nothing in his entire repertoire translated Peterson’s vision of birds more effectively, more artfully, than his field guides, books people could take with them outdoors as they

studied nature first hand. Aided by improvements in ocular devices, these guides gave ordinary people access to an enormous range of information useful to make field identification immediate and accurate. One biographer has estimated that the Peterson field guide system reduces the time to become a proficient birder in a region “from half a lifetime to two or three years.”

Before 1930, bird watching was a rather casual, clubby affair. Questions about identification were usually resolved close at hand after the bird was shot. Most books on birds were multi-volume tomes suitable for the library, although the best of these were handsomely illustrated by such luminaries as Louis Agassiz Fuertes, whom Peterson would emulate and a painter famous for the way he infused images of birds with an intimate naturalism. As a boy, Peterson had consulted Chester Reed’s slender Bird Guide, which contained one bird on each page with accompanying text. Later, Peterson would rely upon Frank Chapman’s many editions of Birds of Eastern North America, a systematic volume that first appeared in 1895, illustrated variously by Reed and Fuertes, among others.

As a student of painting in New York City, Peterson met some of the nation’s best ornithologists and bird painters at the American Museum of Natural History and Linnean Society, including Chapman, the Museum’s curator of birds, and Ludlow Griscom, the acknowledged expert on bird identification through the use of binoculars, not guns. From Griscom, Peterson learned the “philosophy of the fine points of field identification….” By 1930, in association with people in Griscom’s circle, Peterson resolved to do a bird identification book that people could easily carry into the field. It would be similar to Reed’s little book in the Wilson tradition, and systematic, though not as comprehensive, as Chapman’s books. Illustrations for it would be “simple and patternistic, rather like the sketches that [Ernest Thompson] Seton had drawn in Two Little Savages (1903).”

Seton himself was an artist/naturalist who, in a distinguished career, wrote many books on nature. Peterson’s idea culminated in 1934 with the publication of A Field Guide to the Birds, the

first printing of which—over 2,000 copies—unexpectedly sold out in two weeks, despite the fact it cost two dollars and Reed’s Bird Guide was widely available at a cost of only fifty cents. The book was an immediate success, even in the midst of the Great Depression. By today’s standards it was crude, with only four single-sided color plates crowding an average of 20 birds on each [H]. Black and white images dominated. Nevertheless, Peterson had created a handbook that “boiled down” matters so that generally any bird could be distinguished from any other at a glance or at a distance. It was this feature that made the book so popular. Even in hard times people were happy to pay more for it. Despite its embryonic nature, the book also showed evidence of what was to come later, grounded as it was in a basic methodology.

Elegant Design

That methodology remains “comparison and contrast.” Salient distinguishing features were indicated by arrows. Bird pictures were intentionally simplified and shown in the same view and postures, with any difference in stance deliberate, representing a useful recognition trait. Similar species were placed together on one or a few plates to enhance the process of limination. The aim was to provide a quick uninterrupted visual reference that would establish the unique plumage identity of a bird. This is, of course, the genesis of the Peterson method of identification, a system that since has launched a series of over fifty books about the natural world, ranging from astronomy and reptiles to edible plants.

Peterson was concerned that detail would distract the beginner, for at that time most of his readers were beginners. Consequently, he abandoned the realistic portraiture techniques he learned from Fuertes and from studying the works of the nineteenth century Swedish artist/naturalist Bruno Liljefors, a legend in his father’s native country. Instead, he experimented with the most effective method for displaying his drawings. He had an intuitive way of arranging images within a distinctive oriental spatial harmony, perhaps echoing the Chinese print aesthetic informing his work as a decorative furniture painter when he was a teen-ager in his hometown of Jamestown. For his field guide, he began to organize space in a way reminiscent of Japanese scroll ink paintings in the haiga tradition, particularly works by such masters as Niten (early seventeenth century) and Tani Buncho (1763-1840). Haiga is the pictorial counterpoint to the allusive, epigrammatic verse form, haiku; it is the essence of graphic minimalism guided by the (very Japanese) principle of expressing the most by means of the least. Text and graphic image entwine to create and define the space which contains them. This elegant sense of design has become a Peterson hallmark. His use of space is extremely sophisticated; so much so that most readers are unaware of its powerful influence – only its effect. Within this space, however, he constructed the bird images in his early field guides as if they wore simple uniforms bearing special insignia, for that was precisely how he wanted people to see as they used his system.

Mexican Birds and the Third Edition: Challenge and Response

During World War II, the War Department was so impressed with the system that it assigned Peterson the task of designing training manuals for the identification of enemy aircraft. Before he enlisted, he produced a second edition of his eastern guide in 1939 and, two years later, in response to heavy demand, completed the first edition of his western field guide, with more color plates and considerably more birds than for his eastern edition. After the war, he quickly resumed his field guide work. The craftsman in Peterson required that he refine his handiwork continuously. His pride of work, spurred over the years by worthy competitors and the growth of his own knowledge and artistic skill, compelled him to improve each edition.

The post war economy brought Americans discretionary income that would drive the mass markets of the western world. Because of improvements in the economy and in the technology for color processing and reproduction, Houghton Mifflin, his lifelong publisher, gave Peterson a more generous forum for the third edition of his eastern field guide, which he delivered to critical acclaim in 1947. Completely revised, it contained thirty-six new color pages but remained very compact.

His work in the third edition of A Field Guide to the Birds is masterful, beginning with the deceptively effective roadside and flight silhouettes in the frontispiece. Note the way Peterson here uses negative space—the space around the bird images. Everything seems to fit harmoniously, the birds floating on the page yet anchored to it [I]. Recognizing the increasing sophistication of his readers, Peterson made much more extensive use of subtle highlights and shadow to give more of the illusion of solid form. Although there is a vivacity to the birds of this edition, they are still not rendered with great detail, for Peterson continued to feel his method of bird identification would not nearly be as effective if they were: “As they are not intended to be pictures or portraits, modeling of fforms and feathering is often subordinated to simple contour and pattern. Some birds are better adapted than others to this simplified handling, hence the variation in treatment. Even color is sometime unnecessary, if not, indeed, confusing.”

Many consider the plates painted for this edition to be the finest of all Peterson’s bird illustrations. The South Carolina artist, John Henry Dick, felt that they had “arrived at a new art form,” blending the impressionistic with the proper level of detail, harmonizing line, color, form, and space to create the perfect medium for communicating the wonder of nature. The original plates now at the Roger Tory Peterson Institute help confirm this analysis, especially those representing swallows and the thrushes. They pulsate with ordered color, the birds displayed as if by a skilled lapidary, making for a gem-like quality, giving a sense of weight to the schematic image and informing just what we need to know. Peterson’s third edition remained unrevised for thirty-three years.

During this time, Peterson moved his genre incrementally along geographically by illustrating the Birds of Britain and Europe (1954, with later revisions, the last in 1993), the Bird of Texas (1960), and, in 1961, a second edition of Western Birds. After finishing color plates for a wildflower guide with Margaret McKenny in 1968 [J] and for a book about Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World by Dean Amadon [K], he began a collaboration with Edward Chalif for A Field Guide to Mexican Birds (1973). Working in seclusion for nearly three years as the Scholar in Residence at Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Fallingwater,” Peterson painted nearly 550 Mexican species and a total of more than a thousand birds. With this work, Peterson was responding to a serious challenge made to his field guide artistry in 1966 after the publication of Chandler Robbins’ Birds of North America, brilliantly illustrated by Peterson’s friend and artistic rival, Arthur Singer.

By the early 1970s, Peterson’s artistic reputation faced other challenges as well. Numerous high quality photographs of each bird species were now available for field guide illustration. Moreover, the increasing popularity of “nature art” exposed millions to the sophisticated realism of Bateman, Guy Coheleach, John Seerey-Lester, and Lars Jonsson, among others, which in turn raised expectations about the quality of field guide illustration. Paradoxically, the success of the “Peterson System” itself helped cultivate a more discriminating, knowledgeable generation of birders.

With the Mexican guide, Peterson not only responded to these challenges; he turned up the volume, revealing astonishing skills. The bold, dramatic colors and shapes of birds, barely contained in such compressed space, almost slash their way across the pages. For the first time in his field guide format, he painted birds as “…portraits and at the same time somewhat schematic….” Although still in profile and with recognizable, easily comparable features, the birds were no longer two dimensional decals. Rather, many have distinct personas, like those grizzled veterans, the large birds of prey [M], and the presidential jabiru. There is a voluptuous quality to these plates appropriate to life in the tropics. The intensity of the images is such that on occasion they overcrowd themselves on the page, weakening the image-space harmony characteristic of his best work. Nonetheless, this was a profound affirmation or Peterson’s talent, demonstrating he belonged among the first rank of bird illustrators.

The Fourth Edition

Mexican Birds foreshadowed the brilliance of the fourth edition of A Field Guide to the Birds in 1980 and, a decade later, the third edition of Western Birds. Together, they represent Peterson’s art at the apex of his creative powers. The always engaging equilibrium between less-is-more imagery in just-so space, the essence of Peterson’s style, is very much in evidence here. There is a haptic quality about these paintings, for one can almost feel the cascade of his energy as he designed each page with paper cutouts, crafted his final drawings, then laid in varying washes of transparent watercolor and gouache, sealing the work in acrylic glaze. His craft continues to be linked to his method. In these editions, however, he transcends craft and achieves art, resolving paradox by giving structure to gesture with consistent eloquence, harmonizing line, shape, color, space with subtle intensity. With perfect equipoise, he provides just enough detail within the schematic image, balancing it adroitly among other images. He softens edges and gives texture in all the right places while using hard, daring line to secure the bird, holding it for a frozen moment in time. His astute modeling of form allows shadows to chase the light in an animating dance around his best portrayals.

While retaining the abstract functional qualities that made his previous books so effective, nearly every bird here is a nuanced portrait. Even though they remain in profile, with similar size and contours, he captured their characteristic posture and traits—going beyond the form of the bird to reveal an almost intimate personality. Note, for example, the brown thrasher, eastern bluebird (that round-shouldered look), rose-breasted grosbeak, scissor-tailed flycatcher, and wood thrush in the eastern guide—as well as the black-billed magpie and mountain plover in the western guide. Beyond the individual portraits, there are dozens of whole plates that showcase a tapestry of consonant beauty [see illustration N from the Western guide]. Such concord has a purpose.

Fundamental to Peterson’s pedagogy is the stark image of a bird turned to expose markers of its identity and arranged with birds of similar appearance and scale so that direct comparison can take place. This relational organization is the key toward understanding Peterson’s heuristic intentions. For optimum learning efficiency, he limited the number of fifield mark arrows (no more than four, typically two) and, for his recent guides, featured an average of four species to a plate, rather than the ten or twelve in previous editions. With this system, even children can easily discern how the reddish tail of the hermit thrush makes it appear different from the reddish head of its very similar cousin, the wood thrush.

In these mature works, Peterson had made some difficult decisions flowing from his notion of pedagogy as it influenced his strategy of illustration. He affirmed his belief that drawings emphasize field marks much more effectively than photographs. Graphic artists can, he felt, edit the image of a bird to best advantage, in a variety of ways: “Whereas a photograph can have a living immediacy, a good drawing is really more instructive.” Consequently, although Peterson became an excellent and obsessive photographer, he decided not to rely on photographs of birds in his guides. Despite an explosion of field guides in the last thirty years that do feature photography, including a brilliant effort using computer-enhanced photos by Kenn Kaufman in his Birds of North America (2000), it is clear Peterson was correct.

He continued to believe too much detail created a visual overload, undermining the goal of more certain identification. This was true for beginners as well as for most expects. He thought there were diminishing returns in attempts to pinpoint nearly imperceptible differences between species. Better to use supplementary reference guides, which are now readily available on the market. Otherwise, whole pages could be devoted to sorting out plumage distinctions for a single species. Even if this is economically feasible, such a situation would create a learning barrier for most people.

New bird guides like David Sibley’s beautiful, compelling book (2001) derive from Peterson’s original vision. Although they provide a welter of detail about intraspecies plumage variations, they generally add little knowledge beyond Peterson’s guides about identification of species themselves. These books are for the advanced birder, a small number of people who, after many years of learning, know how to identify individual species but who now seek to clarify subtle differences in appearance within species like gulls and hawks, which often require several years of intermediate plumage to attain their adult appearance.

Audubon and Peterson: Not Birds of a Feather

Roger Tory Peterson’s fourth edition of A Field Guide to the Birds represents the summit of his artistic career. The images of birds in this volume—just birds, without background or foliage yet shown in characteristic aspect —are astonishing. In the annals of American natural history representation, they compare favorably with Audubon’s Double Elephant Folio. Whereas Audubon’s works are typically life-sized, engaging the viewer directly in a one-on-one encounter with a dramatic image of a bird, Peterson’s approach in this new edition is much more intimate and relational. Although still insisting that one can only know a bird by comparing and contrasting it with others, Peterson’s mature style of representation now allows a reader, after making the comparison, to focus on an individual bird, savoring its uniqueness all the more. This dialog between the whole and the part, the concept and the detail, occurs on virtually every plate in the fourth edition guide, especially with the tanagers [O], blue finches, icterids [P], avocets [Q] and the very haiga nuthatches [R]. It is a visceral component of Peterson’s art, reflecting as it does a nuanced, contemporary psychology, one more suited to introspection. Audubon’s art provoked a new way of seeing, from a new perspective; Peterson’s art makes one look much more carefully.

Peterson’s work should be considered in the tradition begun with the technical drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, where image and text came so artfully together in the sixteenth century to instruct posterity about Leonardo’s complex ideas on the natural world. Peterson’s field guides also have affinity with Andreas Vesalius’s opus, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, where the union of illustration and text provided students of medicine in the mid-sixteenth century, and for years thereafter, with a vastly improved system for studying anatomy.

Closer to his own time, Peterson’s method is more connected to the tradition of Alexander Wilson than it is with Audubon, more artfully transforming Wilson’s presentation of birds and including information about how and where to see them. Throughout, Peterson’s incisive text is also a marvelous exercise in quintessence. He describes the song of the upland sandpiper as “weird, windy, whistles: whoooleeeee wheelooooooooo.” Chimney swifts are “cigars with wings.” A prothonotary warbler is “A golden bird of wooded swamps.”

Legacy Matters

Introducing the fourth edition of his flagship field guide, Peterson declared the book “has come of age.” In a later article, he wrote: “I’d learned a great deal more about field guides as such and the public had, too. Beyond that, I had a fresh purpose, the result of a bruised ego. Although my bird portraits and limited edition prints had sold in flattering numbers, many people have judged me as an artist by the third edition’s illustrations. Frankly, I’m a much better painter than that. I didn’t want to go to my grave with the third edition as my artistic testament and be remembered primarily as a ‘schematicist.’ In fact, I might just as well admit that the matter of legacy cost me some sleep.”

As part of that legacy, one can see in this work Peterson’s tributes to those who influenced it. Compare, for example, his thrushes with those in his third edition and with Fuertes’ beautiful plate on thrushes in Chapman’s Birds of Eastern North America. Also contrast Peterson’s Says phoebe in the latest western guide with Fuertes’ exquisite watercolor phoebe portrait [S]. And notice how decoy-like he made his scoters and ducks generally, acknowledging the seminal influence of the duck decoys in Seton’s Two Little Savages.

Along with his skills as a naturalist and his intuitive educator’s mien, it is Peterson’s art that makes his work vital for the future. A posthumous fifth edition of Peterson’s field guide appeared five years ago. In the preface, Robert Bateman, perhaps the continent’s most renowned nature artist, discusses what makes the most useful field guide: “Peterson has it just right, to my taste….[Field guide art]…is not easy. I tried it once. I did one plate of curlews for a proposed, but never published, book on shorebirds of the world…. It was agony. Admittedly, curlews, with their subtle mottling, are no picnic to portray. I vowed never to attempt it again, and my admiration for Roger Tory Peterson increased by leaps and bounds.”

Ten years from now, look for a sixth edition of A Field Guide to the Birds, complete in ebook format with film images and bird songs at the press of a button. Then look for Peterson’s painted images of birds as the centerpiece—and hope the editors retain the graceful way he placed them in space.

Field guides about birds continue to evolve in response to change as a series of reciprocities among advancing technologies, skilled international organizations, and the expectations of a public largely made more knowledgeable about the natural world through each iteration of the guides themselves. At their core, however, resides the coordinated talent of remarkable individuals, Peterson first among them.

Peterson’s importance as an artist also has evolved. His greatest achievement came when he was seventy two, but it was a distillation of work begun in 1934, built up in layers with each new edition and leavened by his interaction with other artists, naturalists, educators, scientists, even average birders. Yet, as with much of the art created in the twentieth century, relatively few have even seen his original work.

Prototype and Reproduction: The Importance of Original Work

Meant for commercial distribution, Peterson’s original field guide plates have generally been relegated to a file drawer, living on almost entirely in the reproduced image. The public has seen the work only after it has been transformed with overlaid arrows and text before being reduced one half size and reassembled as pages in books. In 1990, Houghton Mifflin did publish in two volumes The Field Guide Art of Roger Tory Peterson, Eastern and Western Birds. Here the mostly full-sized masterpieces are reproduced in folio at a high level of quality and fidelity to the original image, without the mediation of lines, text, and the pinched spacing of their field guide incarnations. Still, these are reproductions, not the originals.

One of the great challenges for art historians in an era of ubiquitous reproduction is to properly understand the complex nexus involved among an original work, its various alterations in reproductions, and the many contexts for displaying the work that help to generate knowledge about it, as these interact with the sensibilities of viewers. Adding to the complexity is the spate of advertising images gushing from everywhere. Andy Warhol slyly addressed the incessant feedback loop reverberating around the original image, its reproduced image in the marketplace, and its meaning in the minds of citizens/consumers with his representation of a Campbell’s soup can and repetitive portraits of Marilyn Monroe. Even with the fine arts—art made for its own sake– many more people have “seen” the Mona Lisa through reproductions of it than they have seen the original live at the Louvre. Where and how a painting is hung, how its image is circulated through the culture, its changing fortunes over time, and the attitudes people bring to it are ultimately inseparable from its reputation.

In a study of art historians’ methods (“Object, Image, Inquiry: The Art Historian at Work”) by the Getty Art History Information Program and the Institute of Research in Information and Scholarship at Brown University in 1988, eighteen distinguished scholars acknowledged (1) that an original work should be studied for its unique qualities and (2) that the distinction between the prototype and copies of it should be taken into account in any serious study of the work. For most scholars, the prototype is the “starting point of art-historical research….”

An examination of the paintings for the third edition of A Field Guide to the Birds reveals an astonishing luminosity and subtle blushes of detail not seen in reproductions. One can imagine a similar circumstance with the original plates from the Mexican guide and from Peterson’s 1990 Western Birds—along with the fourth edition of the eastern guide.

Without a clear visual sense of what the original works actually are—what they really look like– any meaningful assessment of Peterson’s artistic reputation simply cannot take place. Moreover, absent the ability to compare reproductions with the original work, one cannot detect flaws in them that might alter the visual experience in important ways. Even among the various printings of these editions, considerable variation exists in the quality of reproduction. For example, in the first several printings of the fourth edition field guide, the eastern bluebird appears gray. In the new fifth edition, the color of the blue grosbeak is far off the mark, while the orange throat of the male blackburnian warbler is so pale it makes the bird appear to have had a gender change. At the same time, the color of the tufted titmouse is so brownish it is likely to confound the novice, who will see only a gray bird in the field. One needs access to the original works just to maintain quality control.

To depict an upland sandpiper in the fifth edition of the eastern field guide, the editors removed a serviceable image of the bird Peterson had made for the fourth edition and instead inserted an image from the third edition of Western Birds—one of Peterson’s worst renderings. For some reason, he had trouble painting upland sandpipers, for even his version in the third edition guide was problematic. In response to criticism about this after Western Birds appeared in 1990, Peterson made a new plate for a new edition of his Birds of Britain and Europe in 1993, on which appeared a splendid upland sandpiper. In the ongoing process of revising Peterson’s field guides, knowledgeable editors, with access to all the original plates, will be able to choose among Peterson’s best images.

Considerations

Peterson’s mature field guide art is among the most beautiful conjuries of twentieth century mass culture, and ranks behind only Audubon’s Double Elephant Folio in the annals of American natural history art. It has enormous value to educators because of its heuristic function. And it is an important resource for the study of nature, and for those who would teach the study of nature. It is also an international treasure and should be conserved as a heritage resource. The original art should be carefully displayed as part of a permanent collection in a secure, climate controlled area, maintained by professional curators, archivists, museologists.

Roger Tory Peterson has become an icon of history. His life and works are an integral part of the spirit of our culture, and will be the focus of study over centuries to come. History will judge harshly if his essential oeuvre is not conserved for posterity in ways allowing for a proper measure of the man and an accurate interpretation of his art.

ILLUSTRATIONS

A. Red-winged Blackbird image taken from Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida

and the Bahama Islands, Volume I, 1731.

B. Cardinals et al image taken from Wilson’s American Ornithology, Volume One, 1808.

C. Little Blue Heron image taken from Audubon’s Birds of North America, plate 372.

D. Adelie Penguins from Peterson’s Penguins, 1979.

E. Snowy Owls by Roger Tory Peterson, 1976.

F. Brown Pelicans by Roger Tory Peterson, 1990.

G. A plate from Ernest Thompson Seton’s Two Little Savages, 1903.

H. Frontispiece from Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds, first edition, 1934.

I. A plate on Hawks from Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds, third edition, 1947.

J. Trillium plate from A Field Guide to Wildflowers, with Margaret McKenny. 1968.

K. A plate from Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World, by Dean Amadon and Lester

Brown, 1968.

L. A plate on Orioles from Peterson’s A Field Guide to Mexican Birds, with Edward Chalif,

1973.

M. A plate on Birds of Prey from Peterson’s A Field Guide to Mexican Birds, with

Edward Chalif, 1973.

N. A plate on Cormorants from Peterson’s Western Birds, third edition, 1990.

O. A plate on Tanagers from Peterson’s Field Guide to Eastern Birds, fourth edition,

1980.

P. A plate on Blackbirds from Peterson’s Field Guide to Eastern Birds, fourth edition,

1980.

Q. A plate on Oystercatchers, Stilts and Avocets from Peterson’s Field Guide to Eastern

Birds, fourth edition, 1980.

R. A plate on Nuthatches and Brown Creeper from Peterson’s Field Guide to Eastern

Birds, fourth edition, 1980.

S. Eastern Phoebe by Louis Agassiz Fuertes, watercolor, undated.

12

13