Recent Acquisition: great horned owl watercolor

It’s nesting season for great horned owls in many places in North America. Great horned owls typically lay two to three eggs early in the year, which are incubated by both parents and hatch in about four to five weeks. The young owls begin to climb out of the nest to explore nearby branches about five to six weeks after hatching and learn to fly about nine to ten weeks after hatching. The parents continue to feed the young owls for several months.

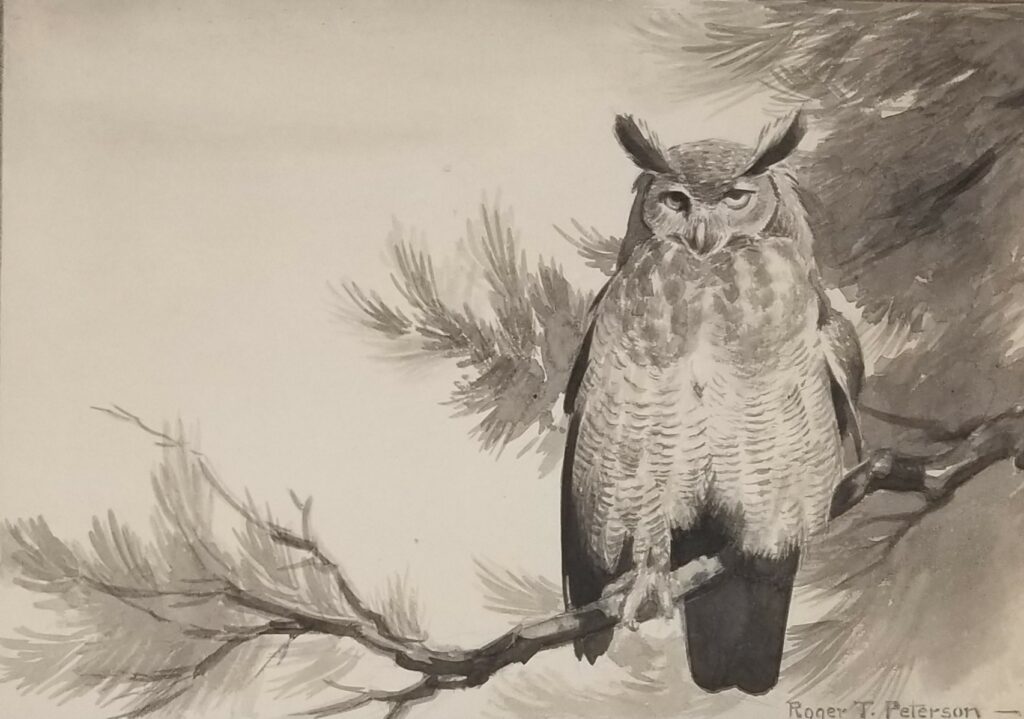

Here at Roger Tory Peterson Institute, we’re excited to announce that we also have a new addition! RTPI has recently added to the collection an early painting by Roger Tory Peterson of a great horned owl roosting on the branch of a white pine tree, which was given to RTPI by Ted Weyhe of Albany, New York. The painting – a monochromatic watercolor – embodies Peterson’s keen observational ability and his passion for birds, as well as demonstrating his innate skill as an artist.

(Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), Untitled (Great Horned Owl), ca. 1930, watercolor and pencil on illustration board, gift of Theodore P. Weyhe 2021.1 © Estate of Roger Tory Peterson)

In this painting, Peterson’s skill is especially evident in the way he uses varying weights and lengths of brushstrokes to replicate textures: we can imagine the softness of the feathers, the delicacy of the pine needles, and the roughness of the tree bark. We see the way in which he has skillfully modeled the owl and the branch using the contrast between highlight and shadow, and how he has used varying shades within the pine needles to give the illusion of depth.

While believed by previous owners to have been painted by Peterson at the age of 12, it is likely that the painting dates to the late 1920s or early 30s when Peterson was a student of painting in New York City. Peterson studied at the Art Students League under Kimon Nicolaїdes, the author of The Natural Way to Draw, and John Sloan, one of the founders of the Ashcan school. Following the Art Students League, Peterson studied for three years at the National Academy of Design, with instructors including Frank DuMond, R.P.R. Neilson, and Edwin Dickinson.

We can notice in this watercolor the influence of Peterson’s academic training, especially in the way that he uses the countour line to define shape. The body of the owl is framed both by its wings and the background in order to create form and structure. By using a countour line in this way, Peterson is able to use minimal shading throughout the body, which in turn creates a soft, airy feeling through the owl’s feathers. We can also notice how Peterson was influenced by the dynamic graphics of Japanese woodblock prints. For example, he uses a strong diagonal for the branch and prominent outlines to activate the composition and draw our eye around the painting.

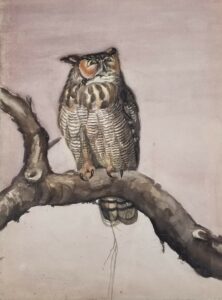

Already in the collection are three similar paintings of great horned owls by Peterson. All are undated watercolors, but are believed to have been painted in the 1950s or 60s. The owls in these later paintings are more active than the stately owl in the early work, capturing the expressive personality of the birds. We can tell by the posture of the owls that they are perching, allowing them to rest while they use their eyes and ears to locate prey. In one painting, the ear tufts are facing backward – the owl might be protecting its ears from the wind, or directionalizing sound.

(L) Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), Untitled (Great Horned Owl), ca. 1960, watercolor and pencil on illustration board, gift of Virginia M. Peterson 2001.51.5.109 © Estate of Roger Tory Peterson

(L) Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), Untitled (Great Horned Owl), ca. 1960, watercolor and pencil on illustration board, gift of Virginia M. Peterson 2001.51.5.109 © Estate of Roger Tory Peterson

(R) Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), Untitled (Great Horned Owl), ca. 1960, watercolor and pencil on illustration board, gift of Virginia M. Peterson 2001.51.5.110 © Estate of Roger Tory Peterson

(L) Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), Untitled (Great Horned Owl), ca. 1960, watercolor and pencil on illustration board, gift of Virginia M. Peterson 2001.51.5.111 © Estate of Roger Tory Peterson

In all three, Peterson has still captured the contrast between fluffy feathers and sharp talons, but he has rendered the birds in the later paintings with a more cartoonish quality. For example, we can notice the prominence of the highlights on the eyes, talons, and beak, as well as greater detail in the feathers and developed shading throughout the bodies of the birds. Despite the stylistic differences, all four paintings embody the way in which Peterson used his art to continually learn about the personality and character of great horned owl, as well as his desire to capture the essence and character of birds.

Get to know the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus)

- Nesting season begins in January/February. (Keep your ears open for mating calls!)

- Female great horned owls are larger than males, but males’ calls are deeper.

- Mated pairs occupy a territory year-round and often for many years.

- Great horned owls are typically nocturnal and become active at dusk, but some have been observed hunting in the afternoon in some regions of North America.

- Great horned owls’ eyes are proportionally some of the largest in the animal kingdom. The eyes do not move in the owl’s sockets and they don’t need to. Great horned owls can turn their heads 270-degrees.

- Their feathers act as insulation against the cold, and they puff them up to keep warm.

- Their feathers also allow them to fly quietly when in pursuit of prey.

- They typically move between high perches when hunting, then glide down silently to grab prey with their talons. Their talons can exert about 28 pounds of pressure, which is how they usually kill their prey.

- Although they often eat small mammals, due to their massive size, great horned owls can prey on birds as large as raptors and other owl species. Many bird species mob a great horned owl if they detect it, and groups of American crows (up to a hundred or more individuals in size) have been observed mobbing a single great horned owl.

- Wild great horned owls often live up to about 13-15 years old and adults have few predators, other than eagles and other great horned owls. Most mortality is related to human activities.

- When threatened, great horned owls take a defensive stance that makes them look larger. They also make a clapping sound with their beak. Click here for an example.